– 23 August 2024 –

Barzillai “19th Century” Bozarth:

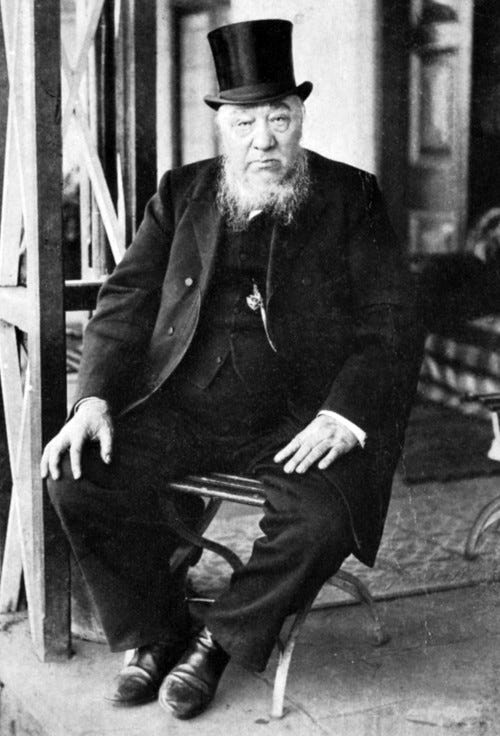

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger — called “Oom” (Uncle) Paul by those who revered him — was president of the South African Republic (Transvaal) from 1883 until the republic’s defeat by Great Britain in the Second Boer War (1899 to 1902).

Kruger was a very shrewd man, though simple, of enormous Christian faith, very much a product of his uneducated, semi-pastoral — but remarkably vigorous — people, and growing out of the wild African land of his time. His life provides perhaps the best example of the achievements that a very uneducated, but nonetheless brilliant, man can accomplish with strength of virtue, natural talents, and humility before God. Like so many other Boers of that time, the only book he read was the the Bible, and he firmly believed throughout his life that this was the only book worth reading at all.

Kruger was born in 1825 in the British-annexed Cape Colony, and as a boy he took part in the Great Trek of Dutch-speaking Boers into the African interior, disdaining British rule. He gradually moved up the ranks as a military leader under Andries Pretorius‘ efforts to build self-ruling Boer states outside of British control, and he headed the Boer military forces as commandant-general for ten years.

In 1877, Kruger became Vice President of the Transvaal, and shortly afterward Great Britain unilaterally annexed the young republic. Kruger was sent to London as part of a delegation to negotiate the restoration of independence, but after three years, these attempts failed, and the Boers launched the First Boer War (1880-1881), which humiliated the British as the first successful rebellion against their Empire since the American Revolution, and at the very height of Pax Brittanica at that! Kruger was elected president of the South African Republic in 1883.

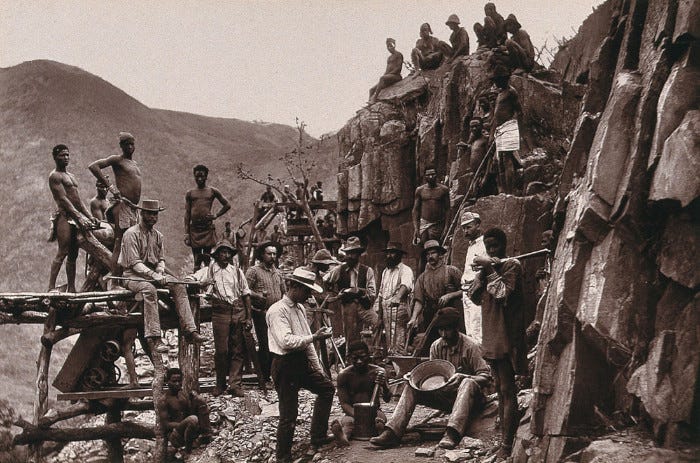

The discovery of vast gold deposits in the Transvaal in 1886 created a gold rush of foreigners, (“Uitlanders” in Afrikaans) into the country, which raised tensions between the Boers and the British, who wished to control the gold under the guise of protecting Uitlander democratic rights.

The following two excerpts, the first by the English “mentalist” Stuart Cumberland and the second by the American Poultney Bigalow, depict impressions of each authors’ meetings with Paul Kruger during the late 1890’s. Each author left with quite opposite impressions, and both gave colorful accounts, but Cumberland demonstrated his own conceit and snobbery as he slandered Kruger, while Bigalow gained an unexpected admiration for the South African president.

Excerpt from What I Think of South Africa; Its People and Its Politics, by Stuart Cumberland, 1896:

WHAT I THINK OF PRESIDENT KRUGER

What do I think of President Kruger? Well, listen. In expressing my opinion of him I do not, of course, ask that every one should agree with me. Every unprejudiced person who reads this can take my opinion of President Kruger for just what he thinks it is worth. Those who have already formed an adverse view of the President may find in what I have written not a little to confirm this view, whilst those Krugerites who, out of thankfulness for past favours, or in hope of favours to come, deem it a sacrilege to even criticize their somewhat exacting patron, can anathematize me to their hearts’ content. I expect it of them, President Kruger will expect it of them, and it is only to be hoped that our expectations, taken from different standpoints, will not be disappointed.

The language of the subsidized Kruger press in dealing with those who do not grovel at their master’s feet is always strong ; in this case it should be lurid. I am really looking forward to extending my knowledge of cuss-words from a perusal of the notices which the “reptile press” of the Transvaal will publish concerning the, in their eyes, damnable heresies I am about to utter. A Kruger organ on the war-path is, I can assure my English readers, more instructive than a slang dictionary; in fact, no slang dictionary has yet been published which contains some of the titbits of vituperative vulgarity in which these organs of public opinion (!) indulge in dealing with those who may politically differ from them.

But to return to President Kruger. It is an age of Grand Old Men, and there is no country without one. Mr. Gladstone is the G.O.M. of England ; Bismarck the G.O.M. of Germany; America’s G.O.M. was Oliver Wendell Holmes, as Victor Hugo was France’s ; Spain’s is Sagasta ; Russia’s was Giers ; Italy’s is Crispi ; Australia’s is Sir Henry Parkes, and last, but not least, Boerland’s is Kruger.

I have met most of the world’s G.O.M., and they have, one and all, been really great ; but it remained until I had the honour of meeting Oom Paul for me to discover that Boerland’s Grand Old Man had nothing in common with their greatness. Since that time, I have been trying to discover how Paul Kruger arrived at the position he holds, and how he became the power in the land that he undoubtedly is.

Success in life lies in knowing how to make use of first chances, and Paul Kruger certainly made use of his first chances. There is, moreover, this much to be said : As in the land of the blind the one-eyed ‘man is king, so in the land of the Boers has it been possible for Oom Paul to become President.

Paul Kruger came into prominence at the time of the annexation of the Transvaal ; and twice he went to England as one of the Boer envoys to lay the alleged grievances of his countrymen before the Secretary of State for the Colonies. In 1880 he formed one of the Triumvirate with Joubert and Pretorius. For more than a year those three patriots ruled the newly-formed Transvaal Republic — until an intrigue made Kruger President, Joubert Commandant-General, and forced the less fortunate Pretorius to retire into private life. Since then, Kruger has sat tight in the Presidential chair, absorbing his many thousands a year salary, and saving in addition a bit out of his “entertainment” allowance. By this time he must, with his land, his commercial interests, and his ready money, be an exceedingly rich man.

Oom Paul has none of ex-President Reitz’s culture or refinement, and absolutely nothing of his savoir faire. Physically he is anything but attractive. His mental gifts are said to be remarkable, but they do not disclose themselves to the ordinary observer. He, I will admit, has a good deal of natural shrewdness ; but it is an animal shrewdness nevertheless. His much vaunted courage, again, is animal. Very much is made of the splendid pluck displayed by President Kruger in the years gone by, in whipping out his knife and cutting off his left thumb — which had been shattered whilst out shooting — without waiting till surgical aid could be obtained. That it was highly courageous none will deny, but it was the instinct of the animal — the trapped animal which gnaws itself free — that prompted him to do it.

In dealing with Paul Kruger, one has not to deal with an ordinary man, and in considering him psychologically, one has to analyze him as a being apart. His ascendency over his fellow-men is very much akin to that obtained by Rudyard Kipling’s Hathor over the denizens of the jungle. It is purely an animal domination ; and with a people in whom animal instincts and animal courage predominate, that domination is not so remarkable after all.

With the Dopper Boers, their Oom Paul “can do no wrong”; but, as I shall show later on, he frequently does, from a political standpoint, the exact opposite to what is right.

But before dealing with President Kruger politically, there is much to be said about him personally.

What struck me most about him was his want of refinement and general slovenliness. One has, perhaps, no right to expect too much in this direction from Paul Kruger, but one does expect something more from the President of the South African Republic, with a salary of ; £7000 a year and “allowances.” With £20 a day, a man, living rent free, can at least dress decently and still have a bit over for such luxuries as pocket-hand-kerchiefs. But President Kruger is the worst-dressed man in all South Africa. I fail to see why he should get himself up like a funeral mute ; but, even if this be his taste, there is still no reason why his woeful garb should not, at least, be decent in appearance. The dust of Pretoria does, I will admit, take a good deal of the shine out of black clothes, but clothes-brushes are cheap, and the President should by this time know something of the cleansing properties of benzine.

President Kruger may be satisfied with his personal appearance, and his faithful followers may be of the same mind ; but, all the same, I do not think it reflects any great credit upon the distinguished position he occupies. In the old days, Paul Kruger, as became a free and unsophisticated Boer, used to go to bed in his clothes : and, to judge by appearances, his earlier habits have not been altogether forsaken. He, moreover, is said to deem a pocket-handkerchief a superfluity. Apropos of this a lovely story is told. When his Honour was about to visit the Queen, it was intimated to him that at Windsor pocket-handkerchiefs were more in use than coat-sleeves, and so a stock of cambrics, to the number of six, was laid in. On his return to Pretoria — so the story runs — the President paid a visit to the store from which the handkerchiefs had been purchased, and handed back four of them — unused — with the remark that he had no further use for them.

In spite of his natural shrewdness, Paul Kruger is preposterously superstitious — a superstition begotten of ignorance.

When I was in Pretoria, representations were made to the President that he should have his thoughts read. The suggestion threw him into a paroxysm of rage, and it was some time before he recovered from the exhaustion consequent upon the use of an extensive vocabulary of epithets more or less uncomplimentary to me. On calming down, he, with that natural knowingness which distinguishes him, proceeded to give reasons why I should not read his thoughts. His mind was full at the moment of important State secrets; and how would it be if, having read them, I communicated them to Mr. Cecil Rhodes? No, the thing was not to be thought of; apart from the wickedness of the whole affair it was not politic. He would keep his thoughts to himself, and I could go — elsewhere.

Seeing that the President stubbornly refused to see me as a reader of thoughts, it was suggested that he might be disposed to receive me as a traveller, who in the course of his travels had met many rulers of States. At first he objected to this, for he failed to see how the man could be separated from the thought-reader; but, at last, his curiosity — and all ignorant, superstitious men are curious — got the better of him, and he consented.

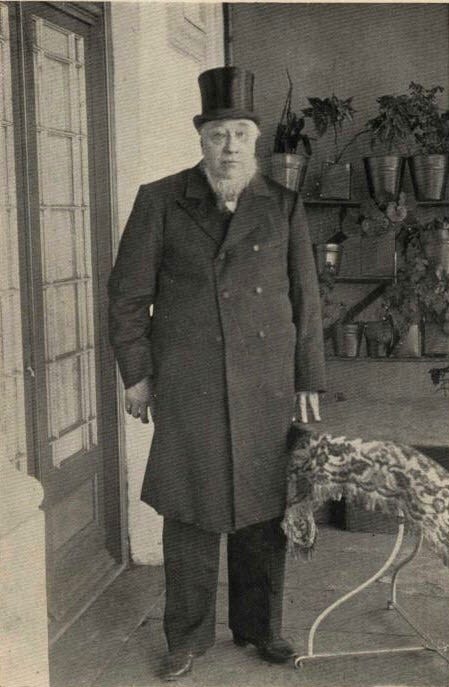

I drove up to his house and took a seat in the small reception-room. Presently the President, attired in his suit of black, a huge Dutch pipe in his mouth, and with his chimney-pot hat on — although a lady was in the room — entered. My friend, who was to make the introduction, introduced me. The President gave me a limp hand, which he instantly withdrew, from fear that contact might give me a clue to his thoughts.

Then he sat down, still with his hat on. After smoking at his pipe for a few moments he took off his hat and copiously expectorated in a spittoon by his side. Not a word of welcome or otherwise did he utter. There he sat in silence, with his eyes averted.

“For heaven’s sake,” whispered my friend, “say something to the old man.” In the family circle Paul Kruger is always referred to as the “old man.”

I said something in English, but the “old man” continued his expectorations unmoved. I had a cut in with German with a like result, and, after a few words in the best High Dutch I could piece together, I gave up the idea of a direct conversation with his Honour the President as a bad job.

“Let me speak for you,” whispered my friend.

“Certainly,” I replied.

“What shall I say?”

“Oh, tell him I am very pleased to have the honour of making his acquaintance.”

This, I presume, the President took as a matter of course, for he did not deign to make any reply.

“What next?” whispered my friend.

“Tell him I think Pretoria a pretty place and the Government buildings very fine, and that I am not a little astonished at seeing such a town blossom out of a wilderness in so short a time.”

This was translated to him, and the reply was a series of grunts, punctuated with expectorations.

And so the one-sided conversation went on, my friend conveying my messages to the President, in Boer Dutch, and the President with Boer grunts replying to them.

It was only when he was asked what he thought of London that the President condescended to make any verbal reply. Even then, to me, it was unintelligible ; the words began somewhere low down in the throat and ended in the spittoon. As interpreted to me it meant “Not much!”

I may say, in parenthesis, that the Boer language is not a melodious one. The words seem to be exceedingly difficult to get off the chest, and I don’t wonder at those who have much to say having frequent recourse to the spittoon.

During the interview, a son of the President popped in and out, but took no part in the conversation ; then his grandson, a highly intelligent lad, who spoke English, came in. Vrouw Kruger — Tanta Sanna — who, I was told, was “tidying up,” did not put in an appearance.

It was suggested to the President’s grandson that I should make an experiment with him in order that the “old man” might have an idea what thought-reading was like. But this the young man strongly objected to ; for, just before I had arrived, his grandfather had warned him against having anything to do with the damnable thing. As a matter of fact, the “old man” had got an idea that I might in some roundabout way get at his own thoughts through his grandson — a method of reasoning which his grandson, although he did not wish to be experimented upon in the “old man’s” presence, was far too intelligent to adopt.

In answer to questions as to the President’s daily habits, the grandson — speaking for the President, who wrapped himself up in a chilling silence, broken only by the pitpat in the spittoon, and the rasping sound of his coat-sleeves drawn across his face — informed me that the “old man” went to bed at eight o’clock and got up at five. On my replying that I, as a rule, went to bed about the time he got up, and got up about the time he went to bed, I got the first smile that had illumined the President’s stolid countenance. It was more of a knowing leer than a smile ; still, it was something to have broken the monotony of that depressing stare. That leer said as plainly as words : “Just what I expected from a person such as you ; the wonder to me is you go to bed at all. In the darkness of the night, when all God-fearing, honest people like myself are in bed, the devil and all his imps are most wide-awake.” Then he looked at his grandson as much as to say: “There, Peter, you see how right I am to have nothing to do with such a man!”

Peter passed the look off, and continuing, told me that, although his grandfather went to bed so early, he frequently -got up in the middle of the night, when rendered sleepless by affairs of State, and came to the room we were then in, to think out matters.

President Kruger may have a very active brain, and may devote the whole of the day and a good many hours of the night to State business, but, all the same, I found him to be a most uninteresting and boresome old man.

After half-an-hour, during which the only words I had got out of him were that he didn’t think much of London, I took my departure. On my rising he seemed quite glad — almost as glad, perhaps, as I was myself to get away — and he gave quite a sigh of relief as he shook hands at parting. The hand-shaking at the last was of quite a different character to that which had marked our introduction ; then, as I have said, the hand was limp and quickly withdrawn ; but this time it had almost a heartiness about it. Its pressure said:

“Read me now if you like, and you will discover that all I am thinking about is the extreme pleasure I feel at getting rid of you.”

But, curious to the last, the “old man” followed me with his eyes, as if seeking for the cloven hoof and forked tail, until I had taken my seat in the carriage outside. As I drove away, I caught a glimpse of him peering cautiously from behind the door. He was evidently determined to see the last of me, and this seeing the last of me gave him, I am sure, considerable personal satisfaction.

Despite his humble origin and general ignorance, there is nothing humble about President Kruger. He is, in fact, an exceedingly vain man ; not vain of his personal appearance — that, at least, would be wanting — but vain of being Paul Kruger. It is hardly enough for him that he is President of the South African Republic ; he wishes to be an autocrat, as autocratic as the Tzar of all the Russias. Against this assumption of political power the more enlightened Boers have for some time past been in open revolt.

What a sad falling off all this is from the Paul Kruger of the old days, the days anterior to 1880, when his hopes were with his barns and flocks, and the “love of freedom” — of which one has heard so much in connection with the Boers — had not materially developed itself! Even in 1881, when that degrading Convention, wrung out of the English, made him President of the Republic, he had, as compared with now, but small ideas of his personal greatness. Then he was but an instrument in the hands of the Lord to work out the salvation of his people. His idea of power was to pose as the patriarch of a purely pastoral and Biblical community, whose chief objects were the multiplication of themselves and their flocks. In this rôle he of course hoped to do well for himself, as a matter of course ; but he had no dreams of the kingly allowance, and the other good things of this earth, that he was afterwards to handle. He looked forward to a peaceful old age, with the certainty that the Almighty would not overlook him when his time came to bid goodbye to the vanities of this wicked world. And now! Well, he, in his opinion, is more an instrument of the Lord than ever, and, as such, he is all the more entitled to the good things of this world — and the next.

President Kruger, thinking himself perfect, is yet willing to allow a modicum of perfection in his fellow Boers, especially those of his beloved Rustenburg ; but the Uitlanders are one and all lost souls. In his eyes, a Boer, no matter how bad, is a brand that has a chance of being at the last moment snatched from the burning ; but with him a Uitlander has no chance whatever. He would seem to think it his mission in life to make the lot of the Uitlander as hard and as difficult as possible; anyhow, he does all he can to make it so. And what would President Kruger have been — where would the South African Republic have been, without the Uitlanders — without the Uitlanders’ money and enterprise?

It is all very well for President Kruger to assert that the South African Republic could do very well without the Uitlander. This is his cry to-day, when the sorely-tried Britisher has helped to fill the Government treasury, and at the same time the unsophisticated Oom Paul’s own pockets. But it was a cry of another kind eleven years ago, when he wanted British help and British gold.

But with the Krugerites one knows how he is always right, and how every one else who does not agree with him is accordingly always wrong. One thing, no man is so impatient of criticism and indifferent to advice as President Kruger.

I was in Pretoria when the President, from the balcony on the Government buildings, made his public promise of burgher rights, plus monetary rewards, to those members of the contingent who had been commandeered in the cruel and infamous campaign against Malaboch. The unfortunate men believed him, and the reptile press belauded the Grand Old Man’s generosity and sense of justice. But I would like to know how many of the men who had been forced to take part in a war in which they had no concern, and who returned to find themselves out of work and homeless, have had the President’s promises realized. Some of them, I know, in their despair took their own lives rather than wait upon the pleasure of this most Christian Government.

This commandeering business was a shameful thing — shameful to the British race, and shameful to the British Government for allowing it ; but of this and many other things in connection with the Boers in another chapter. A few more personal items about President Kruger and I have done for the present.

Although Paul Kruger, the beloved Oom Paul of the pure, freedom-loving Boers, aims at Republican simplicity in all things, unto, as I have already pointed out, his personal get-up, he at times dearly loves to pose before his sycophantic admirers in all the grandeur of his scarf of office, and his foreign decorations. The pompous figure he cuts on such occasions is excruciatingly funny. Fancy, if you can, a venerable patriarch of a rude unlettered people, with all the manners of the veldt strong upon him, in shiny broad-cloth and equally shiny chimney-pot hat, posturing as a Chevalier, or a Knight Grand Cross! Picture this Nature’s perfect gentleman, with his breast loaded with stars and crosses — and not a single pocket-handkerchief about him!

I have endeavoured to convey some idea of President Kruger’s peculiarities, but a complete list of his gaucheries would fill far more pages than it would be either necessary or profitable to devote to them. One little gaucherie however, stands out quite apart, and, as it is too good to be omitted, I will squeeze it in.

Some time ago his Honour accepted the invitation to open a new synagogue at Johannesburg. After the usual preliminaries, he, to the amazement of the Chosen who were there assembled, announced in his loudest tones —

“In the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, I declare this building open.”

After this, the curtain.

Cumberland, Stuart, What I Think of South Africa; Its People and Its Politics, 119-135. London: Chapman & Hall, Ld., 1896.

Excerpt from White Man’s Africa, by Poultney Bigelow, 1900:

PRESIDENT KRUGER

It is not my purpose here to do more than record a few personal notes about Paul Kruger. At a later date I may attempt to fill in this picture by drawing upon the stores of official publications covering the years of hi» public life ; but now I shall seek to give answer to a question that is often heard : “What sort of a man is this grand old Boer?” And let me say, by way of preface, that what I am here penning is partly from the lips of Mr. Kruger himself, partly from his State Secretary, Dr. Leyds, and very largely from intimates who have had the President’s permission to speak in regard to his early life.

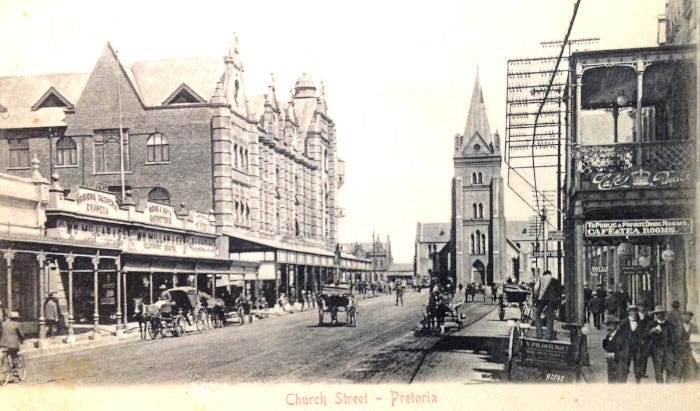

It was on May 30, 1896, that I first set foot in the capital of the Transvaal, named Pretoria, after the Boer leader Pretorius. It was about noon ; the sun was broiling down as it does in Texas ; the broad, dusty streets reminded me of an average prairie town west of the Mississippi, and this impression was further heightened by noting great freight-wagons drawn by sixteen oxen, and scrawny mustangs galloping about, with sunburnt, shaggy-bearded Boers astride of them. There was a flavor of cowboy and sombrero to the scene. With me was Mr. R. W. Chapin, the acting United States consul. He had with him official authority to appropriate the body of an American citizen, take him to Johannesburg, to the bedside of his sick wife, and then bring him back to Pretoria. Mr. Hammond was in the town jail, and Mr. Chapin had cheerfully given up his time in order to do this act of mercy for a woman in distress.

Why Mr. Hammond was in jail is another story. Without pretending to pass here upon the merits of Boer legislation, it did strike me that something must be wrong with the judiciary of a country that found it necessary to treat as a felon such a man as Hammond.

Arrived at the jail, we found the entrance encumbered by dozens of wagons, and learned that President Kruger had that very morning released some fifty of the “Uitlanders” who had been confined as traitors. Hammond was not of this number, so our acting consul applied to the janitor with an official request for him. The jailer, named Duplessis, sent back word that he was too much occupied then to attend to Mr. Chapin, and that he had better return later — in an hour or so. We did as we were ordered, much wondering at this. But on returning to the place we learned that this same Duplessis had meanwhile slipped out himself, taking Hammond with him, for no other reason than that he might thereby himself have a holiday and earn a fee into the bargain. So poor Hammond, after five months of petty torture in the society of black convicts, was on this day robbed of the society of a friend and made to share his sketchy liberty with his jailer.

Sadly we went back to the town, to hear that Hammond had been seen leaving Pretoria for Johannesburg in charge of the jailer, and so our acting consul had a worse than wasted day.

That afternoon, when it was almost dark, a Boer member of the Lower House of Assembly said to me :

“Have you met the President?”

“No,” I said.

“Then come along with me.”

There was a refreshing simplicity about this procedure that suggested a pastoral if not patriarchal form of government. We walked for ten minutes along one of the many broad, un-paved streets of the little town, until we came to five army tents pitched on a vacant corner lot.

“What is that camp doing here in town?” I asked.

“Oh, that is for the President’s sentry guard.”

“Odd,” thought I. “The American President manages seventy millions and doesn’t even have a policeman at his door, and here in a republic of two or three hundred thousand whites the President has to be guarded by soldiers.” Later I found that whenever Mr. Kruger went to or from the government office, he was invariably surrounded by six mounted troopers armed with carbines, and commanded by an officer. The government offices were surrounded by soldiers bearing rifles, and two sentinels paced up and down before the windows of the executive chamber, looking in from time to time to see that all was safe. Of course this room is on the ground-floor. Whether the government indulged in these extravagant military precautions from serious apprehension regarding the President’s life, or whether it did so in order to make the farmer constituents believe that the Uitlanders were plotting to kidnap or assassinate their leader, I do not venture here to express an opinion.

Opposite the five army tents stood a long low house, all the rooms of which were on the ground-floor. A veranda ran along the front, and perhaps six feet of shrubbery separated the stoop from the sidewalk. It was a typical farm – house, such as a prosperous Boer farmer would be inclined to build, and was almost concealed by lofty shade trees. There was no driveway to the front door, no sign that the house contained any but an average citizen of Pretoria. But at the wicket-gate were two soldiers with rifles, who challenged us as we attempted to pass. My friend the legislator said who he was, and that sufficed, for no further questions were asked. The front door was wide open ; we walked into the small and rather feebly lighted hallway, and looked about us in the hope of attracting the attention of a servant. But no servant was to be seen, though we walked through to the back of the house and made as diligent a search as the circumstances warranted.

Then we returned to the front door. To the right of the hall was a reception-room, occupied by a few ladies, who were, I presume, calling upon Mrs. Kruger. To the left was a corresponding room, but the door was closed. Gruff voices I could distinctly hear, and my friend said, in a relieved voice, “He’s there ; it’s all right!”

I thought, “On the contrary, it’s all wrong.” For I had no mind to intrude myself upon Paul Kruger when he was talking gruffly with his fellow-burghers. I had also just learned that the liberated prisoners had come from jail directly to Kruger’s house, and there thanked him for his clemency. I felt that this must have been a hard official day for the aged statesman, and that he was having at that moment another of the many political tussles through which he has had to make his way in order to rule with effect among people like himself.

My law-making friend knocked at the door ; a voice bade us come in, and we entered upon such a scene as carried me back in spirit to the year 1809, when Andreas Hofer met his fellow-farmers of Tyrol in the castle of Innsbruck. But that was long ago, when the first Napoleon was making Jameson raids over every frontier of Europe, and before Africa was dreamed of as anything but a wilderness of blacks and strange animals.

In an arm-chair beside a round table sat Paul Kruger. The rest of the room was occupied by as many swarthy burghers as could find seats. They wore long beards, and gave to the assembly a solemnity, not to say sternness, suggestive of a Russian monastery. My friend led me at once through the circle of councillors, and said a few words to the President, who rose, shook hands with me, and pointed, with a grunt, to a chair at his side. He then took his seat and commenced to puff at a huge pipe. He smoked some moments in silence, and I watched with interest the strong features of his remarkable face. I had made up my mind that I should not say the first word, for I knew him to be a man given to silence. He smoked, and I watched him — we watched one another, in fact. I felt that I had interrupted a council of state, and that I was an object of suspicion, if not ill will, to the twenty broad-shouldered farmers whose presence I felt, though I saw only Kruger.

And, indeed, his is a remarkable face and form. I have seen him often since — during church service, on the street, and in his office — but that first impression in his own simple home will outlive all the others. I should like to have known him in the field, dressed in the fashion of the prairie — a broad-brimmed hat upon his head, a shirt well opened at the throat, his rifle across his shoulder. There he would have shown to advantage in the elements that gave him birth, and lifted him to be the arbiter of his country, if not of all South Africa. Kruger in a frock-coat high up under his ears, with a stove-pipe hat unsuited to his head, with trousers made without reference to shape, with a theatrical sash across his breast after the manner of a St. Patrick’s day parade — all that is the Kruger which furnishes stuff to ungenerous journalists, who find caricature easier than portrait-painting. That is the Kruger whom some call ungraceful, if not ugly. But that is not the real Kruger. Abraham Lincoln was not an Apollo, yet many have referred to his face as lighting up into something akin to beauty. The first impression I received of Kruger suggested to me a composite portrait made up of Abraham Lincoln and Oliver Cromwell, with a fragment of John Bright about the eyes. Kruger has the eyes of a man never weary of watching, yet watching so steadily and so unobtrusively that few suspect how keen his gaze can be. There is something of the slumbering lion about those great eyes — something fearless, yet given to repose. Could we think of Kruger as an animal, it would be something suggested both by the lion and the ox. We know him to be a man of passionate act and word when roused, yet outwardly he carries an air of serenity.

His features, like those of most great men, are of striking size and form, and, moreover, harmonious. The mouth is strikingly like that of Benjamin Franklin in the well-known portrait by Du Plessis. It is a mouth that appears set by an act of will, and not by natural disposition. It parts willingly into a smile, and that smile lights his whole face into an expression wholly benevolent. All those who know Kruger have noticed this feature — this beautifying effect of his cheery smile. The photographs of him give only his expression when ready for an official speech — not his happy mood when chatting with his familiars.

[. . .]

Paul Kruger has a sharp tongue in his head, and a most impartial way of using it. Never an old friend of his did I meet but I heard of some saying or other illustrating this. His strong words run like proverbs through the Transvaal, and, where the law is silent, the Boer is guided by the parables of his President. When, for instance, people warned him against Jameson, who in December of 1895 was preparing his raid upon Johannesburg, he answered them by referring to the tortoise — we must wait until the beast has stretched his neck well out of his shell, then we can cut it off. In other words, he acted towards Jameson and his fellow-conspirators according to this parable — gave them all the time and opportunity they sought, and at last cut the turtle’s head off most completely. On another occasion a deputation waited upon him in order to beg him not to hang Jameson and his comrades. “Bah!” said Kruger, “you are always tap, tap, tapping at the tail of the snake; why don’t you cut his head off?” That is to say: “Why come worry me about Jameson and his filibusters? Why don’t you go for Rhodes, the chief offender?” And again, when on that same May 30, 1896, he received the liberated “reform” prisoners, he said to them, “If a dog snaps at me, I don’t try to punish the dog, but I try to get at the man who set the dog at me.”

These little sayings not merely mark the mind of Kruger, but at this time they illustrate the public opinion among the Boers touching the Jameson raid. That in itself they regard with comparative indifference, but they cherish strong suspicion that behind Jameson stood a very powerful combination of rich and influential men, whose object was to rob the Boers of their independence.

When I first sat face to face with this strong man, I felt much as Kruger himself must have felt on meeting that lion who so strangely interrupted his race with the Kaffir chiefs. He embraced me in his great bovine gaze, and wrapped me in clouds of tobacco. I felt the eyes of his long-bearded apostles boring through the back of my coat. My good legislative friend and mentor was sympathetically troubled as to the reception I was about to receive. It was not a wholly cheerful moment, though I tried to look into his great eyes with some degree of confidence. At last, as though he felt angry at being forced into speech, Kruger said, gruffly, “Ask him if he is one of those Americans who run to the English Queen when he gets into trouble.”

The question was roughly put; the reference was possibly to Hammond and other Americans who had received English government assistance. On the face of it the words contained an intentional insult, but in Kruger’s eyes was no such purpose at that time, and with all his gruffness I could see that there was elasticity in the corners of his mouth. His twenty apostles watched me in silence, and I decided that this was not the time for a discussion as to how far Uncle Sam need apologize for leaning on the arm of Britannia. “Tell the President,” said I, “that since visiting his jail here I have concluded that it would be better policy for an American to ask assistance of Mr. Kruger.” This appeared to break the ice, for Kruger expanded into a broad smile, and his twenty bearded burghers laughed immoderately at my small attempt to treat the subject playfully. It has since crossed my mind that the twenty burghers may have taken seriously what I spoke in jest, but, on second thought, I doubt if much harm could have been done even had they believed me literally. I am sure that each burgher present believed that Americans would do well to invoke Boer protection in case of a difficulty with England.

There was once a council of war in the Transvaal, and one chief asked if any one knew what the English flag looked like. All looked at one another inquiringly. Then up spoke a man who had been at Majuba Hill, and he reported that the only flag he had seen was a white one. Then another, who had fought at Krugersdorp, confirmed his fellow-burgher by stating that the only flag displayed by Jameson was also a white one. I was told by a member of the Transvaal Yolksraad that this is a true story, but, true or false, it has complete currency among the Boers throughout South Africa — so much so that they no longer speak of making war with England ; they refer to such an event as “going out to shoot Englishmen,” as they might go out for antelope or other game. That such sentiments are shared by Kruger I doubt. He has watched the history of Englishmen in South Africa for fifty years, and has fought by their side against natives. None better than Kruger can testify to the personal courage of the average Anglo-Saxon; and if British soldiers have run away from Boers, he knows well that there were circumstances of an exceptional nature to produce so strange a result. But Kruger is an old man, and the men of his generation are passing away, leaving the field to inexperienced patriots who know of English soldiers nothing beyond Majuba and Krugersdorp, just as many French statesmen before 1870 knew of German history nothing but Jena and Auerstadt.

In concluding my first interview with President Kruger he asked me some questions about America, and finally charged me to bear to President Cleveland a cordial message of good-will both for him and for the American people. This was rather a heavy responsibility, and I am seeking in these lines to partly carry out the spirit of my instructions.

After leaving the Presidency I made a house-to-house visitation of all the known book-shops, addressing everywhere the same question : “Have you a life of President Kruger?” Not only was there no life of him to be found in the capital of his country, but no shop could supply me with even a pamphlet on the subject. There were pictures of him, but all from the same negative, and one photographer complained bitterly to me that the President would no longer allow himself to be photographed. I spoke with Boers in high official station regarding the President’s life; they knew nothing of their grand old chief save a few hunting yarns. He was, they said, a man wholly illiterate, who cared nothing for family history or historical record of any kind, and was very angry at such as asked him questions on the subject. Even his State Secretary, Dr. Leyds, told me with regret that he had in vain urged Mr. Kruger to collect material for a biography, but without success. However, one afternoon I was called over to the Executive Chamber, and found to my surprise the President alone with Dr. Leyds, and both prepared to help me in my task. It must have been the hardest piece of diplomatic work ever accomplished by the State Secretary, as can readily be appreciated by any one knowing the temperament of the old Boer. He had before this expressed strong dislike for certain men who had come to see him and had then gone away to make him ridiculous before the public. One of them, for instance, said Mr. Kruger, had called attention to certain stains upon the Presidential waistcoat. Indeed, Mr. Kruger seemed more sensitive on this subject than I should have expected.

However, Dr. Leyds succeeded in convincing him that I had not come to see him for sinister purposes, nor even idle curiosity, and as a result I had with him some memorable moments. He told me many things definitely which I had heard from others and but half believed. For instance, he was but seven years old when he shot his first big game — an age when most of us could scarcely raise a gun, let alone aim it steadily. In those days he lived as a nomad — trecking from place to place over the prairies with large herds of oxen and sheep. The life on the high, open prairie of South Africa is the very ideal of out-door existence, and the men who lead that life should, indeed, all become centenarians, did they not undermine their forces by the immoderate use of coffee and tobacco. At eleven years of age the President, according to his own testimony, had killed his first lion ; and with his thirteenth year he was fighting for his country along with the rest of the citizens.

These facts alone speak for the great physical powers enjoyed by young Kruger, and it is easy to believe them, seeing what a splendid physique he has even now, with more than seventy years behind him. His face today bore to me marks of a deranged liver, as well as impaired digestion, and both these ailments may reasonably be traced to the old gentleman’s proclivity for coffee and tobacco. Had Mr. Kruger led a more simple life in these two respects, he would probably reach his ninetieth year without looking older than he does now at seventy.

[. . .]

Mr. Kruger referred with great pride to his father and mother, both “brave and honorable people,” he said. His father had the distinction of firing the first shot at the English under Sir Harry Smith at Boomplatz, in the year 1848 ; and at the recalling of this stirring episode in South African history, the venerable Kruger seized a sheet of blotting-paper, drew a few hasty lines, and at once, with flashing eyes, gave me a graphic picture of how the British marched up here, the Boers seized that point, the engagement started with this, and ended with that — all told so clearly that the listener had no difficulty in appreciating each move in the little battle.

He was a wild boy, was Kruger, according to his own confession. His friend told me that while engaged upon building the first church at Rustenburg young Kruger was so delighted at having laid the ridge-pole beam that he at once climbed to its highest point and there stood on his head, to the alarm and scandal of the whole community. But, as his old friend explained, Kruger was not a wicked youth ; it was, to be sure, an impious thing to do over a church, but it was done in sheer exuberance of spirits.

Kruger was so clever in the acrobatic line that he could, according to an old friend, stand on his head in the saddle while the horse galloped along. His friend had frequently seen him do this ; and to my closer questioning he said that young Kruger held on to the stirrup-straps by his hands. I have seen Cossacks and cowboys do many clever things, but nothing to approach this feat of Kruger’s. He also was known, when his saddle-girth snapped, to throw the saddle off while in motion and continue the chase. He rode bareback quite as well as otherwise.

As to Kruger’s book-learning there is little to say. His own version is that the little he knows he picked up from a neighboring ranchman, and that was not much. His handwriting is obviously that of a man to whom penmanship is irksome. But those who are in the habit of tracing character by means of chirography will be struck by the persistence and strength indicated by the few letters at the bottom of his portrait. Kruger’s neighbors were no better off than himself so far as schooling went, and we do not say much for him in saying that he enjoyed the best education which the country at that time afforded. That he learned to read and write is in itself creditable, if we reflect that the Boers who trecked northward from the Cape when Kruger was a boy had no houses save their big ox-wagons — or, as we might say, prairie-schooners — and that it was a very rare thing to see a clergyman, let alone a schoolmaster, in those days. Historically it is near the truth to say that the lowest level ever attained by the New England Puritans of 1620 was vastly higher than the best state of the Boer emigrants in 1835. It is only within the memory of the present generation that the Transvaal Boers have commenced to enjoy those educational advantages which the colonists of Massachusetts and Connecticut enjoyed from the very beginning, in spite of red Indian and trackless forest.

But the New-Englander lived in a log-cabin, while the Boer moved with his cattle ; and hard as was the life of an American frontiersman, he was at least in a more favorable position for the learning of his letters than the child of any Boer leading such a life as did young Kruger. At any rate, the President learned to read his Bible, and he reads and re-reads it piously. He has a text for every trouble, and loves to expound its truths both in the family and in the pulpit. People who think little of religion are apt to charge Kruger with hypocrisy, but I can find no foundation for such a charge. He finds in the Bible a strength suited to his daily needs, and the book is as much a part of his life as are his daily meals.

It was not until 1842, said Kruger, that he was confirmed, and then, oddly enough, it was at the hands of an American missionary, the father of Bryant Lindley, who to-day represents a large American Life-insurance Society in Cape Town. Old Lindley was very much liked among the Boers, and as they had no clergymen of their own, he occasionally made journeys among them, for the purpose not only of preaching, but of marrying, baptizing, and confirming. As Kruger was born in 1825, he must have been seventeen years old before he was confirmed — another eloquent witness to the scarcity of clergymen ; for his parents, being God-fearing Boers, would surely not have postponed their son’s confirmation without good cause.

In that same seventeenth year young Kruger filled his first public office, acting as magistrate under the name of field-cornet. He was, to be sure, only filling the place as substitute ; but at the age of twenty he was elected to that post, and from that time on was elected to all the higher grades of the public service, including the post of commander-in-chief and President.

Kruger has been a faithful reader of the Bible, though I could not discover that he read with pleasure anything else. He himself told me that he could recall no book save the Bible that had at all exercised an influence upon him, and this I found confirmed by his intimates. He knows no language but the Boer Dutch, which bears to High Dutch the same relation that Mecklenburg Piatt does to Universitv German. When he visited England he bought an English Bible, and tried by that means to learn our language ; but though he picked up a moderate vocabulary, he never acquired such facility as enabled him to follow a conversation or even write it with ease. Dr. Leyds’s opinion on such a matter I take to be final, for no one can be in a better position than he for knowing the exact state of the President’s literary knowledge.

As Mr. Kruger himself put it, “I had no chance to read books — I was always campaigning or fighting lions.”

I interrupted to ask him which he preferred, African lions or British lions.

“No choice,” said he, gruffly, but with a twinkle in his eye — “they’re both bad.”

Kruger, as I have already said, was never a wicked boy ; but, according to his old friend, there came a crisis in his life when he suddenly experienced a complete change, and, in the spiritual sense, became a new man. The President himself never speaks of this time, and many of his friends were wholly ignorant of this phase in his life. Let me quote the very words of his intimate friend :

”One time he [Kruger] had a struggle with religion, and became troubled in spirit. Of a night he gave his wife a few chapters to read in the Bible, and then went suddenly away for some days, never coming home. This was about 1857 (when Kruger was therefore thirty-two years old). Some men went out to look for him, and when in the mountains they heard somebody sing, but did not take any special notice, and returned, telling that they had heard somebody sing.

“Then they came on the idea that it might have been the President, and they went out again, and found him almost* dying of hunger and thirst ; even to such an extent that they had to take the water away, lest he should kill himself by drinking too much at a time.”

All this is narrated by the man who was then Kruger’s intimate friend at Kustenburg. “When we took him with us,” continued the old friend, “he was so weak with hunger, thirst, and fatigue that we could hardly keep him on his horse.

“Ever since then he showed a more special desire for the Bible and religion. He was a changed man altogether. He lived for religion, telling us that the Lord had opened his eyes and showed him everything. His enemies often talked about this sudden change, but he never took any notice. They often made fun of him, but he let everything pass in silence.

“This incident was the turning-point in his life.”

The place where this happened is near his farm, Waterkloof, near Rustenburg, westward of Pretoria. Those who laugh at Kruger’s piety little know the force of that influence on such a strong and strange nature. It is noteworthy that Paul Kruger became a real Christian at the same age as was the present German Emperor when he first developed his great energies in this direction.

Kruger’s Christianity is not one which he reserves for the pulpit — far from it. He carries his religion about with him, and there are plenty of well -authenticated stories about him to show that his life was a fair reflection of his faith. For instance, he once saw a Kaffir struggling in the river, while other Kaffirs stood on shore as spectators. At once he jumped in for the purpose of saving his life. But the black man lost his head, and grappled Kruger with such violence as to render it more than probable that both would drown together. Kruger was a splendid swimmer, and was able to remain a very long time under water. On this occasion he could only rid himself of the frantic black by total immersion, and so he remained under water for a period of time which thoroughly alarmed those who witnessed the performance; but at last he emerged upon the surface — without the Kaffir.

Another instance of Kruger’s readiness to suffer in the place of another occurred during the troubles with the Orange Free State. Its President, Bosshoff, had made prisoner some Transvaal burghers, who had been under his (Kruger’s) orders. In the language of Kruger’s friend, who was present : “When hearing this, the President at once saddled his horse and rode to the Orange Free State as quickly as possible, informing Mr. Bosshoff that he ought to set those men free and hold him (Kruger) instead ; that those men had merely carried out the orders given by himself as sub-commandant of Pretorius. This was about 1857.” It certainly is not common in modern war for an officer to offer himself a ransom for the men who have been taken prisoners while acting under orders.

The President has a violent temper, and his old friends think that of late years he has had increasing difficulty in restraining it. But quickly as he is roused, so quickly does his passion cool again. One day in 1884 Kruger and Dr. Leyds had a sharp altercation. Strong language was used, for the minister, too, is a man of emotion. At length matters came to such a pitch of passion that Kruger burst out with these words : “One of us must get out.” Of course Leyds said, “Then, of course, I am the one to make way,” with which he took his hat and went home, supposing that his career in the Transvaal was at an end.

In the middle of the night came a rap at the door of Dr. Leyds, and in walked the President. He had saddled his horse and come over by himself, explaining that he had been unable to sleep, and had come to say that he had been in the wrong, and to ask Dr. Leyds that what had passed might be completely buried. This story Dr. Leyds told me to illustrate the President’s generous nature, and, above all, his mastery of himself.

Kruger is a strict member of the Independent Congregational Church. But he is not on that account intolerant. When Dr. Leyds was first asked to become Secretary of State, he declined on the ground that he was not of the same religious faith as the President, but Kruger at once disposed of this plea. “If you are an honorable and able public servant I shall never ask you what your religious views are.” This was a very strong concession for a man of Kruger’s convictions. This generosity of Kruger is notable in his political life. He fights heart and soul for the success of his measures, but when the majority has decided he loyally abides by its decision, and works with it as though it were his own. In this way Kruger has steadily increased the volume of his political followers, and commanded respect from even his enemies.

Kruger was shooting one day when his gun exploded and blew away part of his thumb. The surgeon to whom Kruger finally submitted the case found that the flesh had begun to mortify, and advised amputating the arm half-way up. But Kruger said he could not afford to lose his arm, for then he would no longer be able to handle his rifle. Then the doctor said that Kruger should at least allow him to cut off his left hand. But even this was too much for Kruger. The surgeon hereupon told Kruger that he would have nothing whatever to do with the case, and left. Kruger then got his jackknife and sharpened it carefully, so that it became as sharp as a razor. He then laid his thumb upon a stone, and himself cut off its extreme joint. But, to his great chagrin, the flesh would not heal at that point, as putrefaction had gone already too far. Again he laid his hand upon the stone, and this time carefully cut away all the flesh about and above the second joint of the thumbs and this time the flesh healed and his hand was spared. He now uses his left index finger as a thumb, and seizes small objects between the first two fingers of that hand.

Dr. Leyds almost capped this anecdote by telling me that while in Lisbon Kruger had a toothache, and paced up and down the room, seeking relief in vain. At last he quietly pulled out his penknife and cut the tooth out of his jaw by patience and persistence. What can such a man know of fear? — what can be to him such things as nerves?

It is gratifying to recall now that of all the stories I have heard about the Transvaal President, not one indicates that he is cruel or vindictive or untruthful. Men of all political opinions unite in acknowledging his courage, his good sense, his honesty, his patience, and a host of other estimable qualities. If some member of his family had collected but a tithe of the good things he has said, I have no doubt we should have to-day a volume of table-talk replete with rough wit and homely wisdom — another Martin Luther.

Kruger is unique. There is no man of modern times with whom he may be compared. We must go back to mythical days to find his parallel — to the days of the many-minded Ulysses, who could neither read nor write, and yet ruled wisely and fought successfully. Old Field-Marshal Blucher was a Kruger in his indifference to grammar, but Blucher was sadly devoid of moral principle. Jahn was blunt and patriotic, but wholly lacked Kruger’s spirit of moderation. Cromwell had something of the Paul Kruger, but it soon vanished on the battlefield. The men who framed the American Constitution commanded the respect of their fellow-citizens, but not one of them was a man of the people in the sense that Kruger is a burgher among his fellow -burghers. To compare Kruger with Andreas Hofer is also misleading, for the Tyrolese peasant acted not for his people as a sovereign people, but exclusively for his Emperor as the Lord’s anointed.

Kruger is the incarnation of local self-government in its purest form. He is President among his burghers by the same title that he is elder in his church. He makes no pretension to rule them by invoking the law, but he does rule them by reasoning with them until they yield to his superiority in argument. He rules among free burghers because he knows them well and they know him well. He knows no red tape nor pigeon-holes. His door is open to every comer ; his memory recalls every face ; he listens to every complaint, and sits in patriarchal court from six o’clock in the morning until bedtime. He is a magnificent anachronism. He alone is equal to the task of holding his singular country together in its present state. His life* is the history of that state. Already we hear the rumblings that indicate for the Transvaal an earthquake of some sort. We pray they may not disturb the declining years of that country’s hero — the patient, courageous, forgiving, loyal, and sagacious Paul Kruger.

Bigelow, Poultney, White Man’s Africa, 20-45. New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1900.

Both of these meetings seemed to have taken place around the year 1896, as tensions between the Boer republics and the British Empire were quickly coming to a head. The British fanned Uitlander grievances to the point where the latter appealed to London for negotiations, which quickly broke down, if we assume they were taken up in good faith at all. Realizing the inevitable, the Boers attacked the British in 1899 and started the Second Boer War.

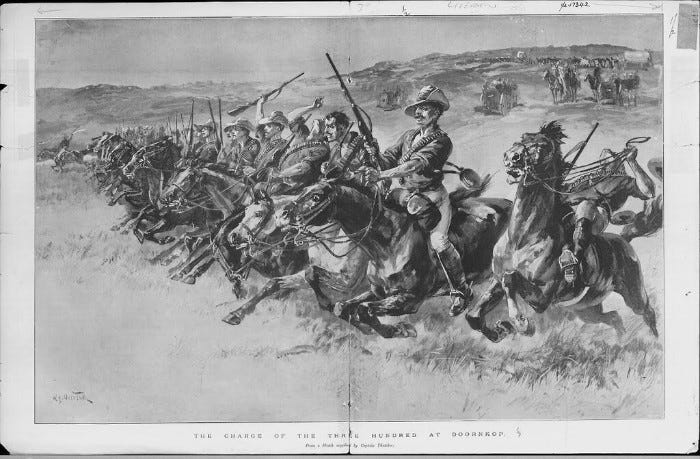

The Boers initially kept the British at bay, winning several victories, but London sent over 500,000 soldiers into South Africa from all over the Empire, fighting a full-scale war against 60,000 kommandos. After a year of courageous resistance, both Boer Republics fell to invasion. Transvaal leaders, fearing Kruger’s capture, urged the president to flee the country and appeal to Europe for assistance. Because his wife Gezina was too ill, Kruger had to leave her behind; she died in 1901.

Historians have debated the need for this departure, but Kruger had proven over the course of his life that he possessed unquestionable virtue; if he escaped the country, he did so in the belief that he was serving the needs of his people. The war was unpopular in Europe and became something of a cause célèbre against the aggressions and abuses of the British Empire. But the Empire was the strongest military power of the time. Many among the Great Powers expressed sympathy to Kruger, but none would intervene on the Boers’ behalf. “Among nations, friendship doesn’t exist; only interests.”

After the military defeat of the Boer Republics in 1900, the war should have ended. But the determined Boer people continued to fight in insurrection for another two years. “Bitter-enders” launched raids and attacks, even as the British rounded up their wives and children into the world’s first modern concentration camps. Only after some five percent of the Boers had died in the camps, most of them children, and thousands of Boer men were scattered in distant prisons throughout the British Empire, did the war finally end.

Paul Kruger died in 1904, broken-hearted and living in exile, his people under harsh British rule.