An Intro to the Generational Theories of Strauss and Howe

Even those who know their history are still doomed to repeat it.

– 1 March 2024 –

Janus:

Sometimes it’s tempting to think that present-day circumstances will just project into the future in a straight line; if not forever, then for the rest of our lifetimes anyway. On the surface, this line of thought seems logical. We get through life by recognizing predictable patterns and projecting them into the future. The cycles of the seasons, the cycles and routines of state and business, the status quo of the world order, etc. Much of it comes down to normalcy bias for most people. (There are also the end-of-the-world doomsayers, but that’s another story!)

The fallacy of this thinking, though, is that people give too much weight to the present time, seeing the past through the lens of the present. Supposedly intelligent people might study a little history, but “history” typically means the last 100 or 200 years or so. How relevant is anything before that? It’s human nature to see the events and circumstances of their own lifetimes, and maybe what we heard from our parents or grandparents, and everything else is filtered through the lens of those experiences.

Any long-term history book is going to give the briefest accounts of the distant past, and maybe some decent coverage of events before the past 100 years, but the closer one gets to the present, the more that these books tend to cover less significant, more recent events. This makes sense; the authors are writing these books for a present-day audience who wants to understand their present times, not to make predictions about the future.

In actual reality and outside of cherry-picked history, time itself moves slowly and steadily and indiscriminately. All sorts of events are happening at any given time, and all these events can be quite relevant to the people of their times but might not have much importance to “history” even a few months later on.

The main question is: how routine are those events? Do they follow recent patterns or do they disrupt or break the patterns? And how do the people collectively react to these “all sorts of events?” Often the level or type of reaction comes down to the collective temperaments of the people at the time.

Another part of historical reality is that, just like nations are real entities, generations are real, definable entities that have common characteristics that set them apart from other generations, even within their own nation. The major events of history arise from the friction between distinct nations and generations. God Himself often works through nations and generations as definable, collective organisms.

Back in 1991, two boomers (William Strauss and Neil Howe) wrote a groundbreaking book called Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. Unlike a standard history book that tries to cover important events that ultimately have the most interest or impact on the people of the present-day, the writers of Generations wanted to show linear social patterns across American history and how they are likely to direct human events into the future. They highlighted historical events to demonstrate this pattern, and they offered some generational predictions about the course that American history would likely take about 80 years into the future (from that time.)

The usefulness of any theory depends on its predictability. Does the premise hold when applied to other areas? In this case, does Strauss and Howe’s predictive model hold up into the future?

In Generations, Strauss and Howe wrote the following back in 1991:

Enter the ‘‘Crisis of 2020.”

When will this crisis come? The climactic event may not arrive exactly in the year 2020, but it won’t arrive much sooner or later. A cycle is the length of four generations, or roughly eighty-eight years. If we plot a half cycle ahead from the Boom Awakening (and find the forty-fourth anniversaries of Woodstock and the Reagan Revolution), we project a crisis lasting from 2013 to 2024. If we plot a full cycle ahead from the last secular crisis (and find the eighty-eighth anniversaries of the FDR landslide and Pearl Harbor Day), we project a crisis lasting from 2020 to 2029. By either measure, the early 2020s appear fateful.

It’s easy to give too much weight to present-day events that seem earth-shaking and historic, but in 2020, several unprecedented, world-altering events took place. 2020 was the year of the worldwide Covid overreaction and global psy-op, where almost every world government acted in lockstop on the same narratives and the same imposed useless surgical masks and experimental MNRA injections. In the midst of the Covid tyranny, the BLM insanity rolled (or more accurately, was pushed) across the West, and the US election was stolen from Donald Trump, highlighting the increasingly violent racial and social divisions in America and the West.

Then, only a few years later, the Russians invaded Ukraine, and the West is reacting more aggressively to that invasion than to anything the USSR ever did during the Cold War, with even Sweden and Finland tossing away their neutrality over it, and Russia casually making threats about nuclear war.

It looks like there is something to this generational theory.

So what’s the theory?

The Strauss-Howe Generational Theory

Wikipedia’s description covers the general idea pretty well:

The Strauss–Howe generational theory, devised by William Strauss and Neil Howe, describes a theorized recurring generation cycle in American history and Western history. According to the theory, historical events are associated with recurring generational personas (archetypes). Each generational persona unleashes a new era (called a turning) lasting around 20–25 years, in which a new social, political, and economic climate (mood) exists. They are part of a larger cyclical “saeculum” (a long human life, which usually spans between 80 and 100 years, although some saecula have lasted longer). The theory states that a crisis recurs in American history after every saeculum, which is followed by a recovery (high). During this recovery, institutions and communitarian values are strong. Ultimately, succeeding generational archetypes attack and weaken institutions in the name of autonomy and individualism, which eventually creates a tumultuous political environment that ripens conditions for another crisis.

[. . .]

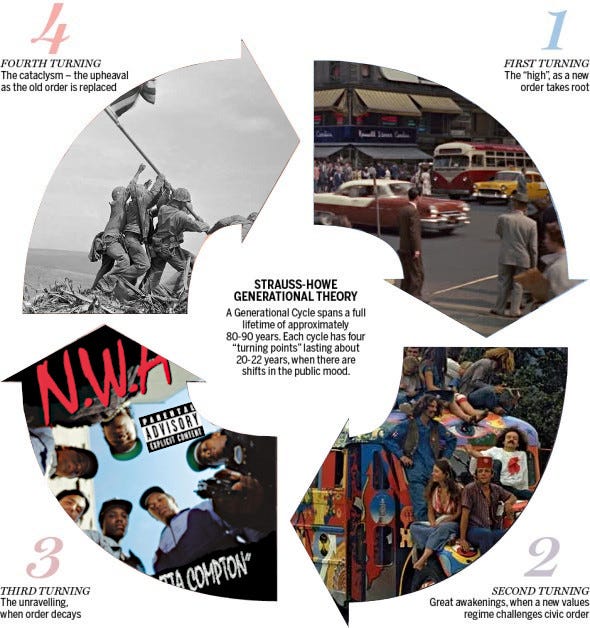

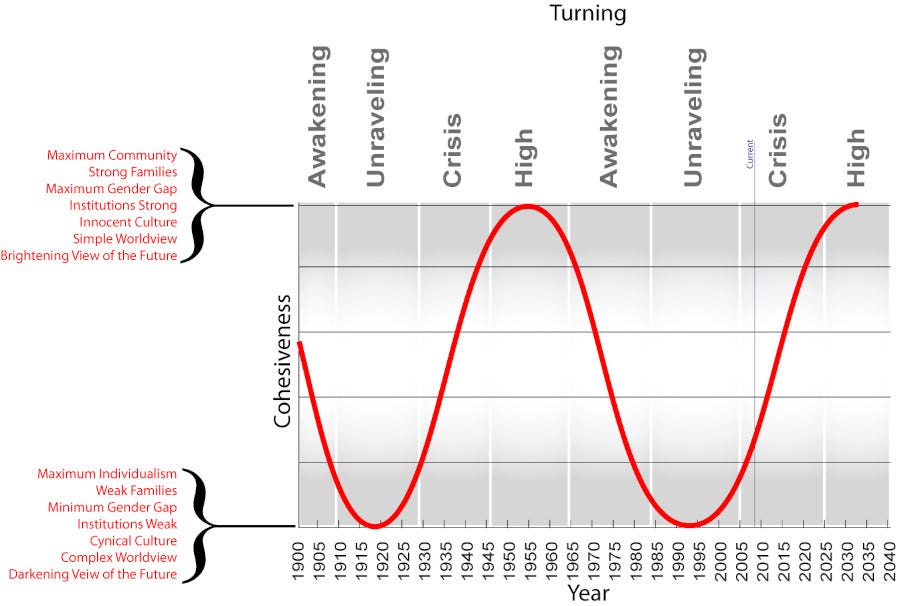

Turnings

While writing Generations, Strauss and Howe described a theorized pattern in the historical generations they examined, which they say revolved around generational events which they call turnings. In Generations, and in greater detail in The Fourth Turning, they describe a four-stage cycle of social or mood eras which they call “turnings”. The turnings include: “The High”, “The Awakening”, “The Unraveling” and “The Crisis”.

High

According to Strauss and Howe, the First Turning is a High, which occurs after a Crisis. During The High, institutions are strong and individualism is weak. Society is confident about where it wants to go collectively, though those outside the majoritarian center often feel stifled by conformity.

According to the authors, the most recent First Turning in the US was the post–World War II American High, beginning in 1946 and ending with the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963.

Awakening

According to the theory, the Second Turning is an Awakening. This is an era when institutions are attacked in the name of personal and spiritual autonomy. Just when society is reaching its high tide of public progress, people suddenly tire of social discipline and want to recapture a sense of “self-awareness”, “spirituality” and “personal authenticity”. Young activists look back at the previous High as an era of cultural and spiritual poverty.

Strauss and Howe say the U.S.’s most recent Awakening was the “Consciousness Revolution”, which spanned from the campus and inner-city revolts of the mid-1960s to the tax revolts of the early 1980s.

Unraveling

According to Strauss and Howe, the Third Turning is an Unraveling. The mood of this era they say is in many ways the opposite of a High: Institutions are weak and distrusted, while individualism is strong and flourishing. The authors say Highs come after Crises when society wants to coalesce and build and avoid the death and destruction of the previous crisis. Unravelings come after Awakenings when society wants to atomize and enjoy. They say the most recent Unraveling in the US began in the 1980s and includes the Long Boom and Culture War.

Crisis

According to the authors, the Fourth Turning is a Crisis. This is an era of destruction, often involving war or revolution, in which institutional life is destroyed and rebuilt in response to a perceived threat to the nation’s survival. After the crisis, civic authority revives, cultural expression redirects toward community purpose, and people begin to locate themselves as members of a larger group.

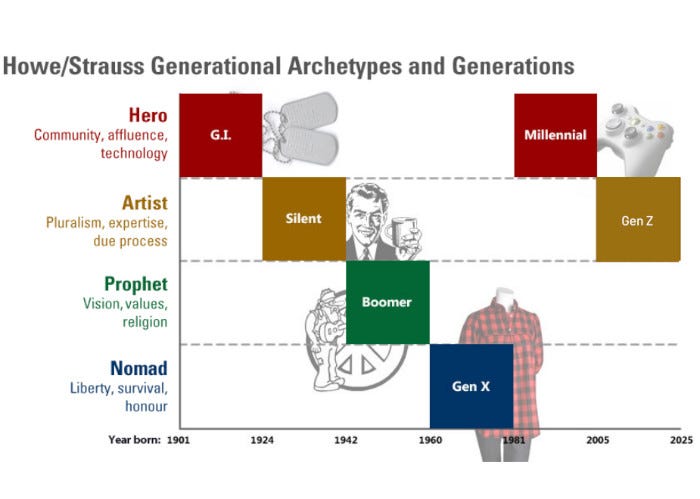

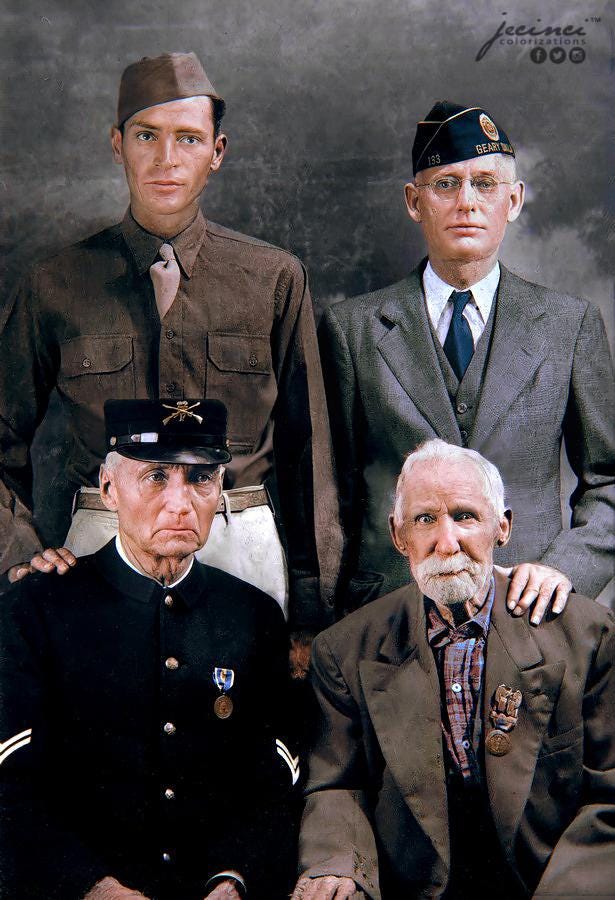

The authors say the previous Fourth Turning in the US began with the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and climaxed with the end of World War II. The G.I. Generation (which they call a Hero archetype, born 1901 to 1924) came of age during this era. They say their confidence, optimism, and collective outlook epitomized the mood of that era. The authors assert the Millennial Generation (which they also describe as a Hero archetype, born 1982 to 2005) shows many similar traits to those of the G.I. youth, which they describe as including rising civic engagement, improving behavior, and collective confidence.

I hate to say it, but if the faggy Millennials are supposed to represent the great saviors of the country, then we aren’t going to perform very well. In fairness, we also have the Boomers as our wise elders, Gen-X as our crusty generals, and the chemically castrated Zoomers as the youth. Not the greatest ensemble. But then, maybe some suffering and strife will do us some collective good, regardless of victory or defeat.

Cycle

The authors describe each turning as lasting about 20–22 years. Four turnings make up a full cycle of about 80 to 90 years, which the authors term a saeculum, after the Latin word meaning both “a long human life” and “a natural century”.

Generational change drives the cycle of turnings and determines its periodicity. As each generation ages into the next life phase (and a new social role) society’s mood and behavior fundamentally change, giving rise to a new turning. Therefore, a symbiotic relationship exists between historical events and generational personas. Historical events shape generations in childhood and young adulthood; then, as parents and leaders in midlife and old age, generations in turn shape history.

Each of the four turnings has a distinct mood that recurs every saeculum. Strauss and Howe describe these turnings as the “seasons of history”. At one extreme is the Awakening, which is analogous to summer, and at the other extreme is the Crisis, which is analogous to winter. The turnings in between are transitional seasons, the High and the Unraveling are similar to spring and autumn, respectively.

[. . .]

Archetypes

The authors say two different types of eras and two formative age locations associated with them (childhood and young adulthood) produce four generational archetypes that repeat sequentially, in rhythm with the cycle of Crises and Awakenings. In Generations, they refer to these four archetypes as Idealist, Reactive, Civic, and Adaptive. In The Fourth Turning (1997) they change this terminology to Prophet, Nomad, Hero, and Artist. They say the generations in each archetype not only share a similar age-location in history, but they also share some basic attitudes towards family, risk, culture and values, and civic engagement. In essence, generations shaped by similar early-life experiences develop similar collective personas and follow similar life trajectories.

[. . .]

Prophet

Prophet (Idealist) generations enter childhood during a High, a time of rejuvenated community life and consensus around a new societal order. Prophets grow up as the increasingly indulged children of this post-Crisis era, come of age as self-absorbed young crusaders of an Awakening, focus on morals and principles in midlife, and emerge as elders guiding another Crisis. Examples: Transcendental Generation, Missionary Generation, Baby Boomers.

Nomad

Nomad (Reactive) generations enter childhood during an Awakening, a time of social ideals and spiritual agendas when young adults are passionately attacking the established institutional order. Nomads grow up as under-protected children during this Awakening, come of age as alienated, post-Awakening young adults, become pragmatic midlife leaders during a Crisis, and age into resilient post-Crisis elders. Examples: Gilded Generation, Lost Generation, Generation X.

Hero

Hero (Civic) generations enter childhood during an Unraveling, a time of individual pragmatism, self-reliance, and laissez-faire. Heroes grow up as increasingly protected post-Awakening children, come of age as team-oriented young optimists during a Crisis, emerge as energetic, overly confident mid-lifers, and age into politically powerful elders attacked by another Awakening. Examples: Republican Generation, G.I. Generation, Millennials.

Artist

Artist (Adaptive) generations enter childhood during a Crisis, a time when great dangers cut down social and political complexity in favor of public consensus, aggressive institutions, and an ethic of personal sacrifice. Artists grow up overprotected by adults preoccupied with the Crisis, come of age as the socialized and conformist young adults of a post-Crisis world, break out as process-oriented midlife leaders during an Awakening, and age into thoughtful post-Awakening elders. Examples: Progressive Generation, Silent Generation, Homeland Generation [Zoomers].

The interplay of events affects the interplay of generations for people at their given ages, and the interplay of generations affects the interplay of events. It’s a feedback loop. Unless some external force interrupts this process, the interplay of events and generations creates this self-perpetuating generational cycle.

This dynamic gets interesting when different nations interact with other nations that exist on different cycles. Minor wars for Americans in Iraq, for instance, might have felt like a critical generational struggle for the Iraqis. It would be interesting to see if Iraq decides to more or less sit the next world conflict out.

Arguably, World War I erupted because Eastern Europe (including Russia) had hit a Crisis period even though the West had not. But the West got sucked into it, and they fought the war with brutal ineptitude and only won against the East because of the West’s superior technology and the East’s internal civil wars. Yet civic institutions and borders didn’t change as much in Western Europe at the end of the war as they so dramatically changed in Eastern Europe and the new USSR. When World War II happened twenty-five years later, the West had reached their Crisis period, and the East was dragged into the war. And in the aftermath, the United States largely ruled the whole West, the Zionist state was established in the Middle East, and European states ended up abandoning their world empires in favor of globalist liberal capitalism.

Over time, and with advances in technology, it seems like nations across the world, more and more, are falling into the same cycle. Because of World War II, it seems like Eastern Europe fell more into the cycle of the West, though the 1989-91 events of Eastern Europe that overthrew Communism echoed Eastern Europe’s previous Crisis cycle. And this alignment of cycles has extended into Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia at the very least, because of World War II and Zionism.

In the past, when nations were more isolated, the interactions of their cycles with other nations with different cycles tended to neutralize their broader effects outside their immediate regions. Small-scale wars created a kind of civilizational or worldwide equilibrium of noise. Yet, over time, and as technologies advanced, the projection of power could grow wider and deeper, so the scale of the conflicts grew larger and forced greater regional alignments in their generational cycles. In modern times, the Western generational cycle seems to have absorbed all of the cycles of the rest. Now, rather than worldwide conflicts neutralizing the effects of other cycles around the region and world, the various world conflicts amplify the effects worldwide and play into ever-growing regional and world tensions.

It also seems like, as most of the world now falls into the Western generational cycle, the differences between the different generational archetypes are becoming increasingly pronounced, with the generations becoming less and less comprehensible to one another (but increasingly share the same culture and mindframe within the same generation from nation to nation.) It’s not crazy to say that Zoomers in Indonesia (for example) have less in common with Indonesian Baby Boomers than they have with other Zoomers in the West.

What generation before the Baby Boomers ever had so much self-awareness as a definable entity? Now every generation has a collective name.

This exaggeration seems to arise from technology that fosters the spread of modernism and liberalism, but also the large scale of so many nations falling into the same cycle seems to have a pronounced effect. The collective moods amplify across the world rather than cancel each other out.

With the combined effects of deepening differences between the personalities of the generation archetypes along with the alignment of most of the world into one generational cycle, it seems likely that world conflicts will grow more deadly and destructive, that the future post-war age of conformity will create crippling dystopias, that the resultant future spiritual awakening and rebellion will create even more self-infatuated and insane religious/ideological fanatics than even the boomers, and that the future unravelings will create even more criminal and antisocial nomads that will make Generation X look like fluffy team-spirit optimists.

In any case, Strauss and Howe’s generational theory seems to be holding up. I personally have endorsed it since the 1990’s, and nothing has led me to doubt the concept since that time. It’s true that there are weenies who talk about everything through the lens of Strauss and Howe, like it’s their religion, but the predictability of this theory shows that it’s a very useful tool to help understand why world events play out the way they do, why people are collectively acting the way they do, and how (and roughly when) these events and moods are likely to shift in their directions in the coming years.

With that understanding, it’s clear that the current crisis mood of most of the world is going to climax soon, if it hasn’t already, but that this mood will calm after the climax plays out, probably around 2030. Afterward, the overwhelming majority of people will cool their jets and accept the new state of affairs (whatever they are). Then about twenty years after the crisis, around 2050, give or take, a self-indulged generation will rise that has no memory of the crisis, and they will revolt against the post-crisis order and the system will gradually succumb to their cultural and spiritual mindframe. Then around 2060 or so, ungrateful, cynical rebels will help break down what remains of the system with their chaotic individualism.

There is the trite old saying that those who don’t know their history are doomed to repeat it. Well, that’s true, I suppose. It’s also true that even those who do know their history are still doomed to repeat it. But at least they can better figure out how to get out of the way.